Interview by Gabriele Naddeo

Illustration by Thomas Borrely

After publishing two EPs and performing at Coachella 2018, Raquel Berrios and Luis Alfredo Del Valle, known as Buscabulla, worked for two years on the duo’s first LP, “Regresa”. They eventually released the record for Domino’s Ribbon Music on May 2020. The album’s title refers to the couple’s decision of leaving New York after 10 years of living there, and getting back to beloved Puerto Rico. The island, an unincorporated territory of the U.S., had to face and still faces issues as an economic crisis, environmental disasters, and political corruption. However, as Raquel tells me on the phone, something is changing, and Puerto Rico remains a magical place to live in, as the band’s very colourful clips show. Mixing salsa, reggae, bolero, contemporary R&B, and electropop, Buscabulla imagined a new Caribbean sound, warm and tropical. A sound that shortens the gap between tradition and innovation, trying to free Latin music of those who want it fixed in its stereotypes.

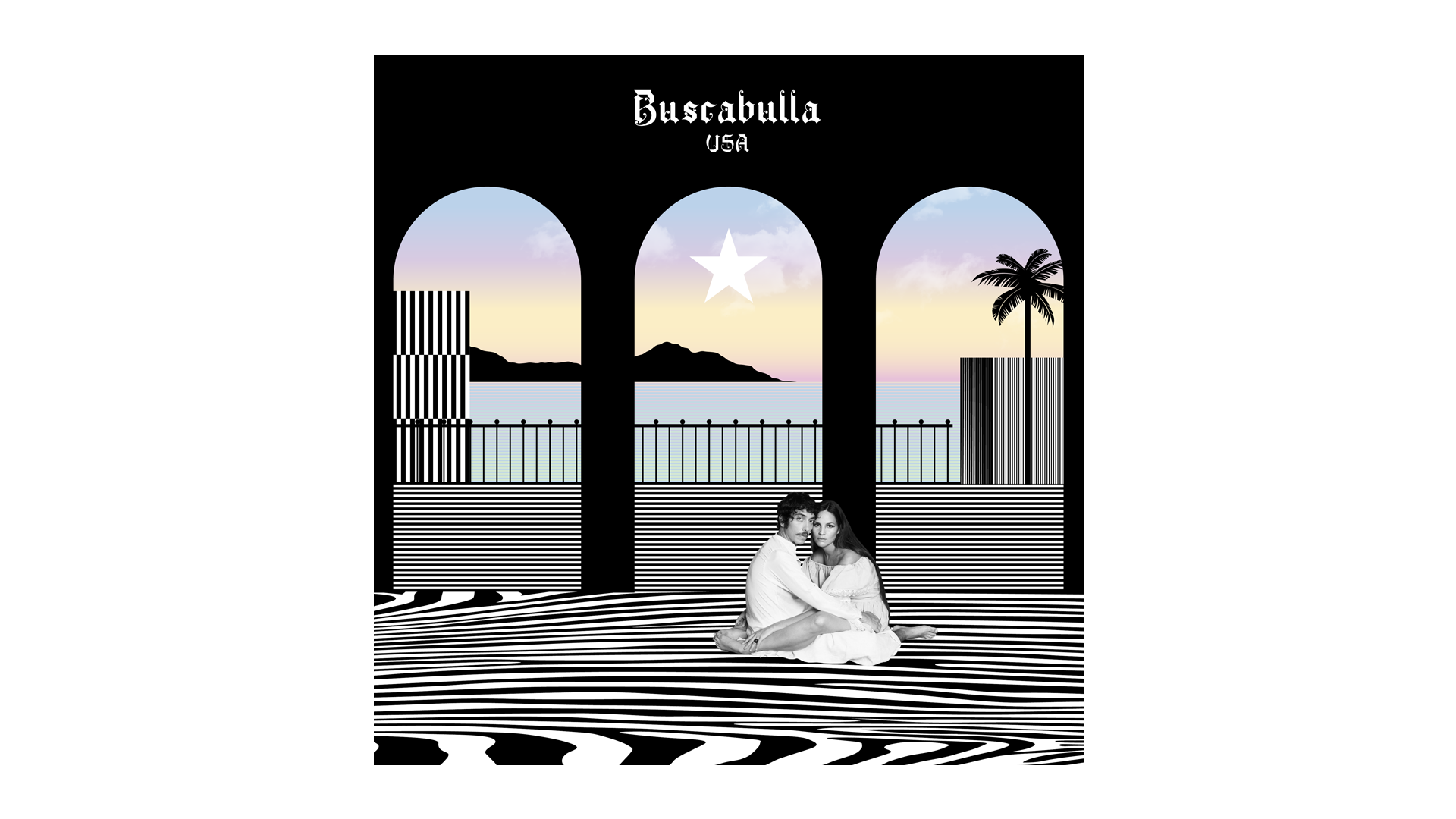

“Regresa” album cover.

I would like to start with the album cover of your record Regresa. There’s a sense of beauty and ruin in it. Could you tell me a bit more about this shot, your dresses, and the meaning behind it?

The record cover was shot in Ponce, Luis’s hometown, in front of one of our favourite buildings that actually is coming apart. Our dresses are traditional Portorican carnival dresses. They are called the vejigantes dresses and are usually worn with masks. We just really picked those because they kind of look royal, they seem like kings and queens’ dresses, but we loved the fact that they are made with very cheap material. In a way, I feel that those dresses represented our hopes and aspirations for a brighter future on the island and for more celebratory feelings. But the idea was also to create a contrast between those elaborate dresses and the fact that both Luis and I are kind of embracing the ruins of this abandoned building, this lonely place which for us also represents how so many young people left Puerto Rico. Like the building, Puerto Rico is in a way in ruin, as we have been in an economic crisis for the past ten years, we have been hit by hurricanes, it is definitely a critical point for our island. So that was our way of representing both something melancholic and sad but also hopeful and emotional.

Frame from the clip of Vámono

The carnival celebrations in Puerto Rico seemed to have been a big visual influence for your record. Apart from the dresses, what’s the story behind the carnival floats? Why do people shake them, as seen in your videos?

Carnival in Puerto Rico is just amazing. I was fascinated a lot by it as it is a great mix of cultures: European, U.S., local cultures. Throughout the years it modernized a lot. Once they paraded with horsebacks, now they use these floats doing wheelies and playing reggaeton. The floats are run by the so-called gangs, namely a group of people dressed the same and taking care of all the decorations. They even put decorations under the floats, so that they can be shown only during the wheelies. There are lots of urban legends about who did the first wheelies, probably 20 or 30 years ago, but no one really knows who started this tradition and when.

Apart from the carnival celebrations, was Beyonce’s Homecoming a reference to the clips of Vamono and Mìo?

Well, we saw it live as we played Coachella 2018, so yes it was definitely a big influence! It was interesting because we started to work on “Regresa” just on that year, so the idea of “Homecoming” as well had a specific sense for us as we just got back to Puerto Rico in 2018.

In terms of sound, “Regresa” beautifully mixes contemporary R&B, Latin, tropical and electropop. The album was mixed by Patrick Wimberly, who also worked for Solange’s “A Seat at the Table” and Blood Orange’s “Freetown Sound”. How did you want the record to sound like? Which were your musical references?

I think that we wanted something to definitely sound more Caribbean and really wanted to connect more with Puerto Rico. We just really wanted to be very emotional and evoke the island in a way, and our transition from New York to Puerto Rico for sure. However, there was not a set plan, we just started the songs and then the ones that made sense are the ones that we included in the record. But once we put them all together and heard them we realised there was a pattern and there was a story that has been told through the songs that we included in the record. I think that having Patrick mixing and finishing it was a sort of a cycle, as we were first in New York, then went back to Puerto Rico, and finally back to New York just to finish the album. Patrick was in a band that had a great influence on us, so it felt like something that we had to do, but also felt that we were still in a transition between New York and Puerto Rico.

Usually what I do when I am working at a record is making Pinterest boards where I put all of my musical interests, so I can keep them all in one place, like YouTube videos, songs etcetera. I can’t make playlists because I like to combine YouTube as it gives you also a visual impression of whatever music you are interested in, which is why I find Pinterest the best way for me. For this record, I really wanted to merge Caribbean sounds, like salsa, bolero, reggae, and Carnival sounds. I already knew that these influences were there, but then I also had all these other influences ranging from Japanese experimental music to Somali funk and African music. I think ultimately we just wanted to sound kind of tropical and warm and try to imagine what the new Caribbean sound would be like. There are definitely also influences from reggaeton and reggaeton production. Depending on what we wanted the songs to be about we decided and mixed different genres.

During the last couple of decades, Latin music gained enormous success worldwide mainly because of reggaeton, and Puerto Rican artists played a massive role in this sense. However, during the last few years, other Latin genres are gaining success too. I am thinking about artists like Helado Negro, Lido Pimienta, apart of course from the urbano sound of Bad Bunny, 070 Shake, Princess Nokia, Rosalìa etcetera. Do you think that labelling all these different artists, including yourselves, as Latin artists is a reduction just because you all sing in Spanish? Is it an out of date label or on the other side it is something to be proud of because it shows the fact of being part of a bigger community?

This is an interesting thing and mostly has to do with a primary view of music because if you think about it nobody calls it American music. But it’s interesting how you don’t really talk about American music when you talk about all genres made in America. You talk about hip hop, country music, rock etcetera, which could all be linked to American music in a way, but you don’t call them American music at all. And the fact that we are called Latin is sort of viewed from a point of view of otherness because you know everybody knows that the gatekeepers of the music industry are Americans or maybe European, and so Latin is seen as some kind of minority to a certain extent. So it’s definitely weird especially for us artists that are making mainstream Latin music because it feels like we’re in this really weird point where people don’t really get what we are doing. Especially, it always feels that everybody wants you to make stuff that sounds Latin, that looks Latin, but what is that it’s only really coming from stereotypes. So when you’re Latin and you’re trying to make weird music, as I call it – namely music that might get out of the Latin stereotypes – it feels that people are not ready for it. But I think it’s mostly an issue of representation and I feel that the more we give platform and visibility to these weirdo artists the more would become normal to hear those sounds.

For instance, to me, I feel like Almodovar really changed what Spain looks like through his really quirky way of filmmaking. It took time, but now when you think of Spain you also think of Almodovar and in a way I think that we’re still building this for ourselves. The way that you proceed Latin America must definitely go beyond the salsa, the ayayay, the reggaeton. There’s so much more that no one says and I feel like we’re just sort of building that so now this alternative sound in Latin music is becoming also part of the understanding that you have of Latin music. But I think that we still have to work really hard for that. We’re still building that category if you wanna say that.

And what do you think of the Latino, Latinx, Latine debate? I think that it’s all very confusing. Right now in Spanish, we’re having a big debate on inclusive language, but the inclusive language has not been approved yet by the royal language institute. I do understand why new generations are asking for new terms to define us. I am not completely convinced that one is better than the other, I feel we’re still in a transition and that it’s also hard because in a way there are a lot of different people that are considered Latin. Spain colonised like a whole continent and there are so many different cultures under this umbrella term and on top of that you also have the American-Latinos. So I think it’s very hard to classify us under one label when we’re literally composed of so many different countries and cultures. What is true I think that it is going to be a complex thing and there’s no right or wrong answer. Probably it’s kind of similar to what is happening with the European Union, but I am sure that most people still believe that they are just Italians rather than European. The question is: beyond language – and beyond the fact of having been colonised – what is the thing that we all share together? What really brings us together?

You lived in New York for 10 years, before deciding to go back to Puerto Rico, a decision that is at the foundation of your latest record. I was reading that the number of Puerto Ricans living in the U.S. is higher than the number of Puerto Ricans on the island. Why did you move to New York, how’s it like living in New York and why did you decide to go back? Luis and I both moved to New York for different reasons. I had a background in architecture and wanted to move to study textile design. So I did my master degree in Rhode Island and then got a textile job in NYC. It’s also a place I always dreamt about going. I felt like I was an artist, I loved music and the arts so it was the place for me where I wanted to go. Puerto Rico is a small island, so as soon as I went to New York I felt like a fish in water, I felt like I was in the right place. And it was in New York that I had my textile job, that I started to work as a DJ, that I worked in record stores and eventually was the place where the band was formed. So in a way the reasons that I went to New York came true. Luis kind of had similar dreams, he moved to New York to study engineering and sound production, to make music and he also was in bands. Which is how we met and the main reason we went there. Now the reason we came back it’s because we always dreamt of coming back. When I left Puerto Rico I left with still one foot on the island. Puerto Rico is a very special place, it’s a small tropical island with amazing beaches and people, it’s not an easy place to live, but it’s definitely fun. It doesn’t function at the same time that New York does.

New York is such a harsh place for Caribbean people – you know the cold, the non-stop working and the not being able to be close to nature. It’s a tough place and that has really been weighing on us. The New York life was really hard – we had day jobs, we had a baby, we had a band. Like playing gigs, having to get your daughter from the babysitter, then unloading all of our equipment and instruments, then driving around finding a parking space, then waking up the next day at 6am to go to work – it was a tough life and we dreamt of coming back. You know, Puerto Rico is cheaper, we have family close by, it’s easier, the weather is nice, it’s a good place to bring up our daughter and we always dreamt of having our home studio and just making music from home. Then now we live just next to an airport which flies to NY, Texas, Miami – so we thought that was the right moment to move after we had a band, an audience and signed a record deal.

There’s a famous Gabriel Garcia Marquez quote saying: “Life is not what one lived, but what one remembers and how one remembers it in order to recount it”. How did you think about and tell about Puerto Rico while living in New York? And what’s the reality that you found once got back to the island? I do feel that when you’re far away from Puerto Rico you’re put under a spell. I think that in a way it’s a magical island that when you’re away from it it makes you idealise it. So you can only really remember the sweet parts, the bliss, the celebrations – Christmas time here is so beautiful! – the way that people socialise. So I think that when you’re away you kind of forget that there are loads of things that are not great about the islands. There is a lot of crime, our politicians are corrupt, we’re in a really serious economic trouble, so there are no many job opportunities, abandoned buildings etcetera. So when we came back it was definitely a reality check. Even though we were really happy to be here and together with the family it was a very big change coming from New York when you have everything that you need, food, pleasure, entertainment and you come back and there’s not that much that goes on and loads of young people are leaving. For the first few months, it was really hard for us. After all, it was also a place we’ve not been for ten years, so for example, many people we knew moved away and we felt kind of lonely too. We were starting all over again, we moved to a town that is far away from the towns we were both originally from. So it was a hard transition.

How is life in Puerto Rico today, about two years after you decided to move back? What do you do for a living apart from Buscabulla?

That’s pretty much it, we’re 100% dedicated to music now. When we moved back we got a record deal and we decided we’re going to live up of this and we made the change and so far so good – knock on wood – but definitely this year has been crazy. I mean imagine that we made this huge decision, we moved with our daughter with the idea of making music full time and then after working two years on the record the pandemic just explodes. I couldn’t believe it. It would have been definitely a better year if we would have been able to tour, but luckily so far it’s going good. We put out the records, it got great reviews and it felt like the pandemic gave the record a completely different meaning. Like in a way people have written back just saying that this record saved them from depression during the pandemic.

A loud noise on the background interrupts Raquel. She explains to me that it’s the sound of the vehicles that politicians rent during election time.

That’s the perfect excuse to talk about politics then. Puerto Rico has a peculiar political situation, being an unincorporated territory of the U.S. What do you think about it? Did you publicly support a party and/or a governor for the 3rd of November’s election? And why?

As for the Democrats and the Republicans in the U.S., we really never had other parties apart from the two major ones. But now in Puerto Rico there were actually two very good candidates not from the popular parties. One is from the independence party and there’s another very good candidate from a new political party that just formed. So we felt like we really didn’t want to publicly support one of those two because we felt they both were really good and we didn’t want to influence people to choose one rather than the other.

Are you talking about Alexandra Lúgaro and Juan Dalmau? Yes, those two. They’re really great, they both performed really well in the debates. They represent the sensibility that both Luis and I have for the island. Anyway, I think that the fact that there are two good alternative candidates to the major parties means that things are changing in the island. To me they sort of represent what Bernie Sanders represents in the U.S. He didn’t win but you have a big movement forming and I think we’re only going to see those movements get bigger and we feel the same in Puerto Rico. These new candidates are really strong and people are starting to gain followers.

And what do you think about the referendum asking to be an official part of the U.S.?

The Progressive Party, which believes in statehood, pushes this almost every four years, and it’s just funny because it feels like a joke. In the U.S. they keep saying we’re not going to consider this right now, this is not in our interest, but in Puerto Rico this political party wants to keep pushing this and use public money to keep on making these referendums. We had so many of these and nothing ever happens – I think they use it as a political strategy, I think they use it so people think they really believe that might happen. What we really think is that the Progressive Party just wants the money of the U.S., but when the time comes to really have statehood they would be scare shit of it. We think they want to manipulate people with the statehood dream.

Luis always brings up a very interesting point. He believes that in the next 50 years Latinos are going to be such a strong force that it could be possible to have Latinos actually running the U.S. I mean I am sure that someone like AOC, who also has a Puerto Rican background, could be president of the U.S. and that would be really interesting, it would be a game-changer. Similarly, we felt that our success as a band came because the Latin community is growing and becoming more central in the U.S., so people were asking for more Latin music and Latin projects. We had definitely benefited from that growth, but I think we all have to be really careful with what we want to represent as artists and Puerto Rican, not to be manipulated by the companies that now try more and more to sell their products to the Latino community.

Speaking of the Puerto Rican community, one last question: could you tell me a bit more about the PRIMA Fund (Puerto Rican Independent Musician and Artists)?